All the names you never hear about

Anjali Sachdeva and other brilliant women writers who never quite get the attention they deserve

*The original version of this post was published on Patreon on January 20, 2022. Thanks to Adrian Rennix for editing this post! You can check out Adrian's terrific (and free) newsletter about immigration policy here.

I’m fascinated by the process that turns some writers into household names, and others into “oh, I’ve heard of her…I think?” It doesn’t seem to have anything to do with talent, good reviews, awards, even the right literary friends. Book sales count for a lot, probably more so than critical acclaim. Genre fiction has its share of stars whose books are highly praised, regularly win awards, even sell fairly well—and are largely ignored by the community of supposed fans. Connie Willis, as I wrote in the now-defunct Current Affairs, is “the most famous science fiction novelist you’ve never heard of.” Nalo Hopkinson, whom I wrote about in my last recommendation post, is another famous science fiction/fantasy grandmaster that not enough people have read, and whose name many supposed SFF fans may not know. Both Willis and Hopkinson rarely appear in top ten or top twenty lists of the best writers of the genre: there are few spots for women in these lists, usually only Ursula Le Guin and Octavia Butler, occasionally N.K. Jemisin or a wildcard like Anne MacCaffrey. Once in a while you may run across a longer list that makes a greater effort at gender parity—and yet Willis, despite winning more Hugos and Nebulas than anyone else, is almost always missing.

Joanna Russ (also criminally missing from these lists) could tell you why this happens. Women’s writing is, and has been for centuries, suppressed, belittled, maybe briefly praised, and then forgotten. This tends to go double for women of color. It’s important to note, however, that this isn’t solely a matter of identity: sometimes it’s also that the stories certain people are writing, and the techniques they may be using, rub uncomfortably up against dominant narratives of what is possible or important or desirable in fiction.

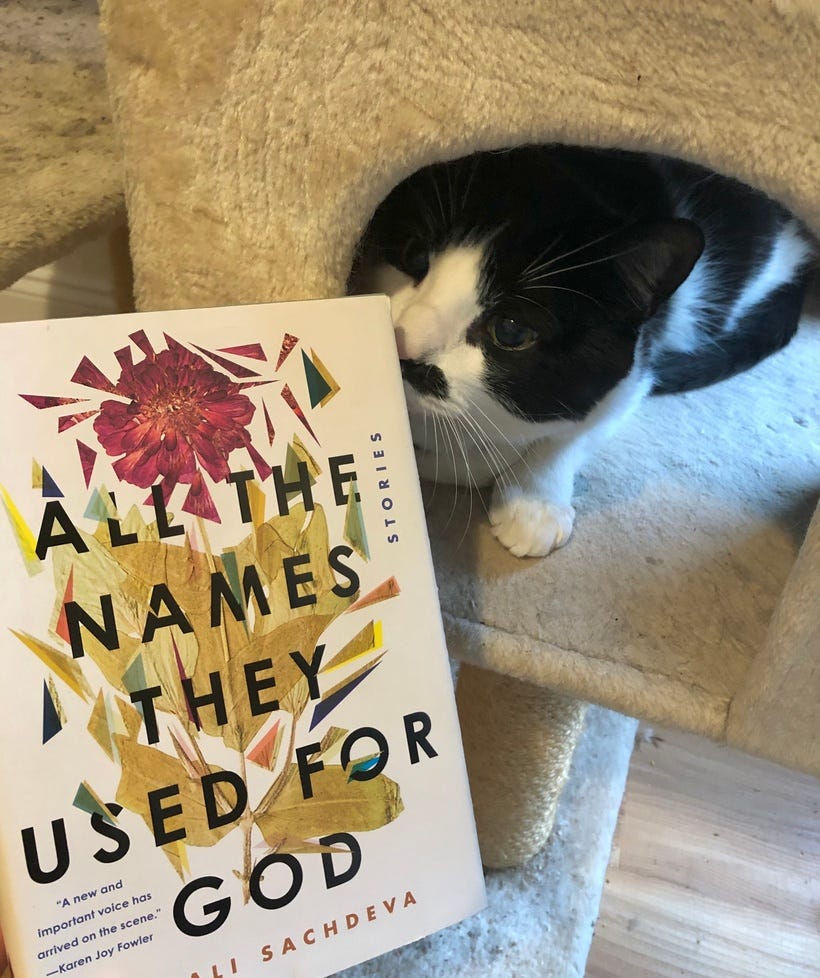

This is a very long way of introducing Anjali Sachdeva, who published an absolutely astonishing book of short stories in 2018. The collection, titled All the Names They Used For God, consists of nine stories, which can only be described individually, not together. A young woman in the 19th century has a strange existential experience alone on the prairie; John Milton speaks to an angel; kidnapped Nigerian schoolgirls escape their Boko Haram captors; a modern fisherman falls in love with a mermaid. There’s a scifi story featuring genetic manipulation, which is great, but don't miss the weird historical fiction about a man with glass in his lungs and a stone that might be magic. Each story is entirely different than the one that preceded it. The settings are different; the genres are different; the voices and characterization are utterly different and remarkably real, every time. It’s a virtuoso performance. After each story you can hear a reverberating silence, as if a master violinist just lifted their bow off the strings.

I think about Sachdeva every time someone raises the question “is it ok for people to write characters unlike themselves?” because from an aesthetic perspective the answer is clearly “yeah obviously it’s fine if, like Sachdeva, you’re good at it.” When it comes to writing characters who are unlike the author, the discussion tends to be theoretical and subjunctive: “if I were to, what would happen” or, after a cancellation “okay, THIS writer wrote two-dimensional and cliched characters, but what if I—” etc. These concerns came up recently thanks to Hanya Yanagihara, whose novels were eviscerated in Vulture by Andrea Long Chu. The Vulture essay is a terrific pan, if you’re into that kind of thing (I may write about the psycho-economics of the takedown as a literary form in my next long post, it’s been bugging me), but Chu also specifically attacks Yanagihara, who is not a gay man, for writing about gay men. Chu specifies that writing about gay people when you aren’t gay isn’t inherently wrong, that “perhaps the great gay novel should move beyond the strictures of identity politics; Yanagihara has stubbornly defended her ‘right to write about whatever I want.’ God forbid that only gay men should write gay men — let a hundred flowers bloom. But if a white author were to write a novel with Asian American protagonists who, while resistant to identifying as Asian American, nonetheless inhabited an unmistakably Asian American milieu, it might occur to us to ask why.” I haven’t read Yanagihara, so I take no particular side in this fight, but I think it’s interesting that we only ever bring up “the right to write” particular characters in a negative context like this: i.e. when we think the writer shouldn’t have done it. Chu doesn’t think Yanagihara’s gay characters are poorly-written, exactly, but that her marked tendency to make them suffer “betrays a touristic kind of love for gay men.”

I’m not generally a fan of this kind of psychological-biographical criticism—teasing out the author’s True Feelings is usually uninteresting to me (Brandon Taylor just wrote a very good essay about this). Maybe, if I read Yanagihara’s novels, I would develop the same suspicions as Chu about her private motives, but it’s hard to conclusively prove something about the interior life of someone you don’t know, especially as reflected through fiction, aka interesting lies about people who don’t exist. One of the things I like best about Sachdeva is that I don’t know—and can’t know—absolutely anything about her through her fiction. Her characters are too different from each other, her settings and genres too varied to point at much in the way of a consistent preoccupation. Shakespeare was good at this (Keats famously pointed this out about him) and in fact so good at it that people still argue whether Shakespeare’s plays were actually written by him or someone else. In the age of autofiction (and the self-insert-not-quite-autofiction-but-we-all-know-let’s-get-fucking-real fiction) it’s rare to run across an author who gives you nothing about themselves, who treats fiction is an art of lies, of inhabiting the interior world of the characters so absolutely that nothing of the writer’s selfhood remains.

Now, obviously there are complex questions of identity and power here, who gets rewarded and punished for what kinds of storytelling, who has access to publishing and being published, etc. But when someone like Sachdeva shows up and demonstrates that you can actually write anyone, anyone at all—she ought to be one of the first names that comes up in these writing-the-other conversations, and she isn’t, because her virtuosity represents a challenge, not an answer. When it comes to writing and identity, surface-level conversations are much safer than real ones; the argument remains more comfortable as a hysterical abstraction than a proved reality. “What if I wrote characters from a different background than myself and people didn’t like it? Look at what just happened to Hanya Yanagihara!” This skips over the real panic, which is every writer’s panic: “what if I wrote it and it legitimately wasn’t good?” The more interesting criticism of Yanagihara, in my mind, isn’t whether a non-gay man writing gay men’s suffering is immoral, or allowed, or what the author may be thinking in her secret heart; it’s is she any good at it? Does she write it convincingly, powerfully, believably? Is the reader able to suspend disbelief and operate as though these horrible events are really happening to the characters, or are we unable to let go of the boring reality that the whole thing is just made up? Is the writer hitting false notes or true ones? Is this a virtuoso performance, or amateurish and self-indulgent?

Anyway I might read Yanagihara someday, though her books don't really sound like my sort of thing. Suffering, like characterization, like horror, is sometimes best with a light touch. The titular story in All the Names They Used For God is the one about the Nigerian girls escaping Boko Haram, and what happened to them afterward. In the hands of a lesser writer, this story would have been trite and headline-grabby; it would have laved its tongue over their awful, distant, foreign suffering. Maybe part of what it takes to become a household name is just this: to emphasize suffering, to make a point of the stakes and your personal distance from them. But if you instead inhabit suffering, inhabit difference, then you may end up doing something that other writers might not like very much. You might show them how it’s done.

I don't know if you've heard of Dorothy Dunnett before but I hadn't until I stumbled across her in a second-hand bookstore. She wrote one glorious epic about the real Macbeth (and did some breakthrough research about the guy in the process) and two STUPENDOUS historical series, the Niccolo and Lymond chronicles - the latter follows the exploits of a 16th century Scottish nobleman who enters a room like this: "Lucent and delicate, Drama entered, mincing like a cat."