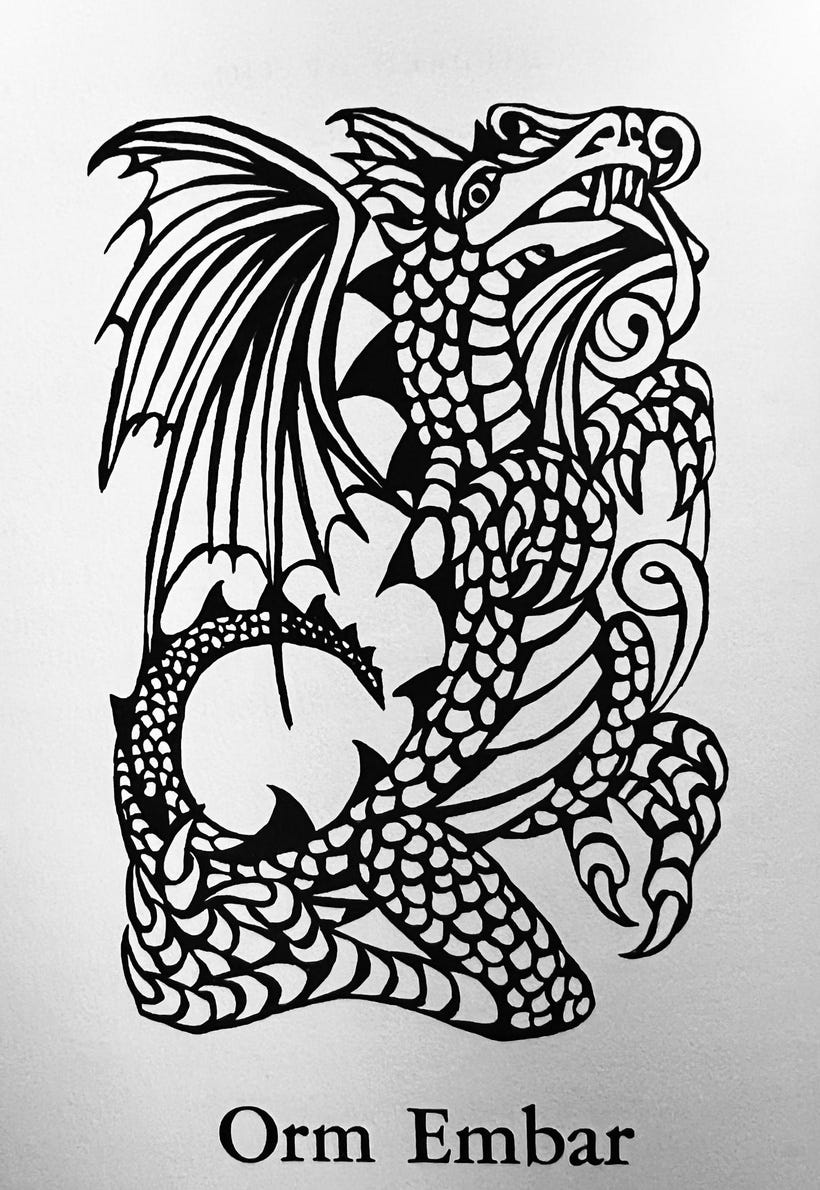

I have seen dragons on the winds of morning

which is why I can't stand all this cynical corporate fantasy TV

*The original version of this post was published on Patreon on September 23, 2022.

It ought to be the best time imaginable to be a science fiction and fantasy fan: and yet, I find I have become a hipster. Of course art isn't somehow magically better when it’s enjoyed by a smaller percentage of the population, but niche status does help guard the things y…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lyta's List to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.