*The original version of this post was published on Patreon on January 6, 2022.

In a better world, Nalo Hopkinson would be discussed a hell of a lot more. She’s not lacking for brilliant books and important awards: her novel Midnight Robber was nominated for the Tiptree and a Hugo in 2000; her short story collection Skin Folk took the World Fantasy Award in 2002. Last year, Hopkinson was named the “37th Damon Knight Grand Master” which is one of the most prestigious honors in SFF (and yes, also sounds like the title of a futuristic chess genius who’s really into dueling.) It’s not that readers and critics don’t talk about Hopkinson, exactly, but there’s a muffling effect that sets in, especially for women writers, especially for writers of color, especially for SFF writers who push the boundaries of the genre, and—most especially—a decade or so after these writers' most famous work has been published, awarded, sighed over for its bravery and originality, and pushed aside for some newer and often safer thing.

I almost mentioned Hopkinson’s The Salt Roads in my previous recommendation post, but hesitated, because while it certainly qualifies as “a book to read in hard times” it’s also extraordinarily special and deserves a little more attention. Experimental novels are often difficult to describe, and The Salt Roads is no exception. We have three major narratives: one set among Haitian slaves in the 18th century; another set in Paris in the mid-19th century, specifically in the debauched underworld frequented by the poet Baudelaire (our protagonist is his mistress, the real historical figure Jeanne Duval); and the third is set in Egypt in the 4th century, where a sex worker named Thais is about to become a saint. And then there’s a fourth narrative, which flows in and out of the others like water: the story of a goddess.

Books that confound genre are theoretically celebrated, in our supposedly avant-garde literary culture, but if a book confounds genre too much, then no one quite knows what to do with it. Is The Salt Roads historical fiction, or fantasy, religious fiction, or something else? It was nominated for a Nebula, and won the “Gaylactic Spectrum Award for positive representation of LGBITQ characters in speculative fiction.” There are queer characters, and straight characters, and tragedy, and romance, and laughter, and disease, and jizz. It’s a heavy book, tearstained and waterlogged, unashamed of human fluids.

But for all that The Salt Roads is concerned with human beings and their bodies, it’s also concerned with the gods, who are not as separate from humanity as one might think. If you were forced to boil The Salt Roads down to a single set of questions, it would be: “why did the gods of Africa abandon the enslaved Africans to the predation of white colonizers? Why do they still abandon them?” It’s ultimately a novel about the problem of evil, a problem for which many, many answers have been offered and I’ve never found one I liked, because (at least for me) they always rely on something too neat, too abstract, too far away to explain the actual bloody facts of human misery. I don’t want to give away any spoilers, but The Salt Roads provides the best answer to the problem of evil that I’ve ever come across. And it succeeds in that because Hopkinson isn’t cute about evil, or gentle about history, or glib about hope. She doesn’t rationalize the suffering of the body—the characters are located violently in their bodies, their damp and leaking and diseased and drowning bodies. And it’s there, in their bodies, and their minds which are an inseparable part of their bodies—not some distant realm of abstraction—that the gods find them.

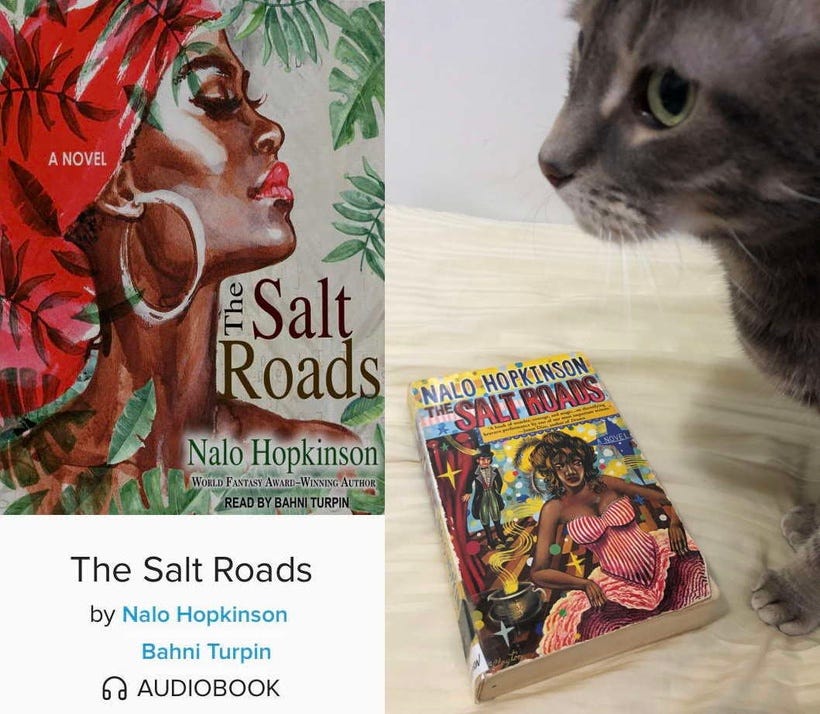

The Salt Roads is, sadly, out of print. If you can find it on audiobook, I highly recommend reading it that way—I first listened to the version read by Bahni Turpin, and she was magnificent. Otherwise The Salt Roads is available as a used book on Alibris with the funky old cover or as an ebook through Open Road Media with the lovely but less interesting new one. And if you want more Hopkinson after that (and more funky covers) I adored Sister Mine.