It’s been “statement time” all week. Just about everybody has issued a social media post or a press release explaining their exact position on Israel/Palestine. Individuals, nonprofits, brands—my favorite is the unnamed company that emailed Wall Street Journal advertising reporter Katie Deighton with the following A+ lede:

This Substack is supposed to be a fun newsletter about arts and culture, so I don’t have much to say about global atrocities. I think it’s generally okay to avoid making a statement on a topic if you’re not a subject expert, and I’m not a subject expert on the Middle East. But I still feel a certain amount of social pressure (by which I mean internet pressure) to say something here. Partly because of the common social media premise that silence can only mean complicity or silent agreement with power and violence, but also partly because any time Israel commits an atrocity, or an atrocity in response to an atrocity, individual diaspora Jews like me feel pressured (or put pressure on themselves) to express an opinion—to avow or disavow, to say “well I support this but not that,” to make sure everybody knows precisely where we stand.

This expectation, which is at least partially self-inflicted, has antisemitic roots (one Jewish person isn’t naturally linked to or responsible for the actions of Jews in another country), and it also surrenders to some of the worst of Zionist expectations. It presumes that diaspora Jews must feel a meaningful connection to Israel, a sense of Israelis as “us,” and Israel in some way as “home,” even if it’s a home we’re ashamed of and feel compelled to disavow. I don’t really feel this way about Israel, even if I feel required to say something about it all the same. I’ve mentioned this before, but in the diverse immigrant neighborhood where I live it’s common for my neighbors to ask where I’m from-from, despite the popular internet belief that this is a rude question; I often prevaricate, and say “Eastern Europe, a long time ago” rather than launch into the currently tetchy subject of Russian and Ukrainian territorial claims. But I never bring up Israel, and never even imagine it. I’m not from or even from-from Israel; I’ve never been there; I have no plans to visit. In college I did briefly intend to do Birthright Israel—I’d justified it by imagining I was going to take a cold, journalistic approach, focusing on what the guides would or wouldn’t say about the Palestinians. But then my non-Jewish boyfriend said, “wait, it’s called birthright?”—and as soon as I heard that word, really heard it for the first time, I realized how impossible it would be to remain objective or get anything useful out of a blood-and-soil propaganda tour. So I dropped the idea and spent that summer visiting my boyfriend (and reader, I later married him.)

According to Jonathan Greenblatt of the Anti-Defamation League, Jews who are not Zionists and have no special love for Israel are “hate groups” and “the photo inverse of white supremacists.” (I guess by “photo inverse” he means photo negatives? Is he making a statement about…skin color? Weird choice, Jon.) Efforts like the ADL’s to reimagine Zionists as the real Jews and the rest of us as self-hating frauds are reflective of a much older division within Jewish culture, which usually played out between Zionist, Hebrew-reviving, often upper-class Jews from Germany, and diasporic, Yiddish-speaking, usually lower-class Jews from Eastern Europe. (If you’re interested in this history, and the way this cultural division was leveraged into the formation of Israel, Hannah Arendt goes into some detail about it in Eichmann in Jerusalem). The cartoonist Eli Valley has also explored this rift through his “Israel Man” and “Diaspora Boy” characters, who are basically the two kinds of Jews as perceived by the ADL: there are true heroic manly Zionist warriors and then there are the fragile fake assimilated babies of the diaspora who are out of touch with their true identity and really just need to make aliyah (move to Israel) and become heroic manly warriors too.

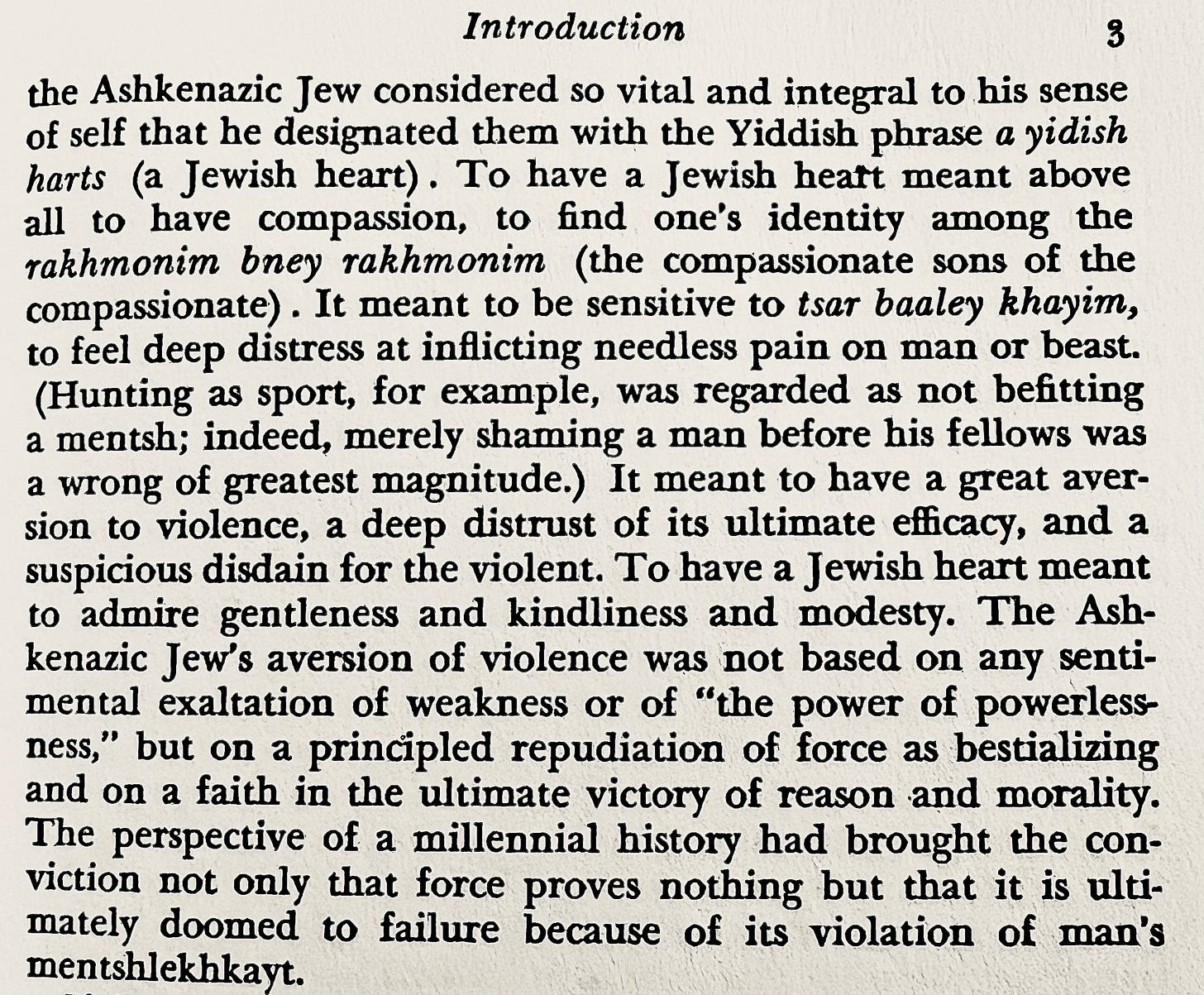

It’s very difficult to look at a religious/ethnic culture, even your own, and make definitive statements such as “this is legitimate/this is not legitimate” or “this is who we are/this is not who we are.” But I look at Israeli warrior culture, the ethic of kill or be killed in a world of mindless violence, and I don’t know what that is. I don’t recognize it. It’s got a certain Klingon cosplay vibe, I guess? Being super into Star Trek is, at least, familiarly Jewish. But other than that, Israeli warrior culture doesn’t have anything in common with the culture I was raised in; it doesn’t look or feel culturally legitimate or connected in any way. Diasporic Yiddish-inflected civilization doesn’t have a warrior ethic: it’s nonviolent, and in fact adamantly so. I actually just ran across a great summation of the Yiddish attitude toward nonviolence in Joseph C. Landis’ introduction to The Great Jewish Plays (1972), a collection of the best Yiddish theater of the past century. The heart of the value system of Ashkenazic (Eastern European) Jewish culture, according to Landis, was a belief in being a mentsh (a good person, a moral person) and in creating an atmosphere of mentshlekhkayt (good or moral action). Violence and vengeance and even interpersonal cruelty could never be part of this, as Landis explains in this remarkable passage:

Wonderful, right? Now compare it, both in ideology and in word choices, to this since-deleted tweet from the official IsraeliPM account:

What the hell even is this tweet? What culture does it come from? 19th century race science? Low-rent fantasy novel bullshit? Curtis Yarvin-inflected 4chan posts combining 19th century race science with low-rent fantasy novel bullshit??? Whatever it is, it’s totally alien to the Ashkenazic “principled repudiation of force as bestializing” and “faith in the ultimate victory of reason and morality.”1 It’s not something that a person devoted to the virtues of mentshlekhkayt could ever think, let alone type, if only because we would be forced to publicly shame them for saying it, which would just be a shande for everybody involved.

So yeah, whenever Israel attacks or is attacked, I don’t believe that I have a personal stake in it, beyond general horror at the scope of human cruelty, and the U.S. government’s role in perpetuating rather than alleviating the violence. I live in the U.S., and I’m from-from the Yiddish diaspora—from people who repudiated war on principle, and made jokes, and wrote really cool plays. I’m not clear on how the Israeli government thinks they can keep going indefinitely with this law of the jungle, kill-or-be-killed nonsense. I’m heartened by the fact that Netanyahu’s poll numbers tanked after the initial attack, because if you maintain an open-air prison on the premise that it keeps the people outside the prison safe, and it doesn’t, there’s really no point to having you around (or the prison itself, for that matter).

I do feel some connection to Israeli leftists who have been advocating for peace and justice for decades (and there are a lot more peace advocates in Israel than some U.S. leftists—of the type that views Israel solely as a psychological dumping ground for personal colonialist guilt—have been willing to admit.) Some Israelis whose family members were killed in the initial attack have called for vengeance, but others like leftist activist Noy Katsman, whose brother Hayim was killed in the attacks on October 7, have refused such an easy mindless response. As Noy said to the huge crowd at their brother’s funeral: “Do not use our death and our pain to bring the death and pain of other people and other families.” This refusal to pile atrocity upon atrocity feels more culturally familiar to me; it’s based on a fundamental distrust, as Landis puts it, of the efficacy of violence. This distrust is unrelated to the Christian “turn the other cheek” approach, arising instead from the logical and practical truth that mass murder, mass torture, and mass imprisonment, gets us exactly nowhere, and provides safety and freedom to no one. A gently judgmental “nu? so what happens after you kill somebody?” is just pure distilled Yiddish diasporic excellence, and it’s been considered inauthentic in the face of militaristic Zionism for too long. Until (and unless) that nonviolent culture wins out, I don’t know who these people are. Don’t ask me about them.2

Vulcan cosplay is obviously a whole other thing, since Leonard Nimoy imported elements of Ashkenazic culture into his performance, including the famous split-fingered gesture.

Credit for the cover/final image goes to Max Berger, who posted it on Bluesky, and to Travis Dawry and drosnthl who helped me source it to the cover of Revolutionary Yiddishland and before that to a Yiddish poster created in Kiev in 1918.

Love you, love this!